The Redemptions of Iyov and Zion

A powerful midrash describes that when Yirmiyahu returned to Yerushalayim after the destruction, he met a woman who was crying unconsolably. After a brief conversation, she introduces herself as the embodiment of “your mother, Zion,” who lost all of her children. Yirmiyahu immediately responds with words of consolation:

From Iyov I took his children, similarly from you [Zion], I took your children. From Iyov I took his gold and silver, similarly from you [Zion], I took her gold and silver… and just as I returned and comforted Iyov, similarly I will return and comfort you [Zion]… in the future I will build you as the verse states “God is the builder of Yerushalayim.”

A truly moving and powerful midrash.

At least two questions emerge from even a cursory read of this passage. First, what is the meaning of God’s comparison of Zion to Iyov? How does Iyov help us understand the suffering and redemption of Zion? Second, it is surprising that Yirmiyahu jumps immediately to consolation. In a parallel story that appears in our kinnot, Yimriyahu meets the female embodiment of the Jewish people and his first message to her is to repent, not a declaration about the future redemption. After all, the setting is in the immediate aftermath of the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash and one would think that the appropriate message would include a call for repentance.

One possible approach to this midrash teaches us volumes about the nature of Yerushalayim and the people who are connected to it. The story of Iyov revolves around the axis of the meaning behind his suffering. The book opens with God Himself testifying that “there is none like him on earth, a sincere and upright man, God-fearing and shunning evil.” Even after his suffering and encouragement from his wife to curse God, Iyov rejects this approach and says “Shall we also accept the good from God, and not accept the evil?” It is difficult to understand what Iyov did to deserve this fate.

The midrashim and commentators struggle to identify textual cues for Iyov’s sin. According to one source, Iyov only served God out of fear but did not reach the requisite levels of love of God. According to another, he only did not curse God externally, but internally he did sin. Ramban argues that Iyov himself was perfect, but his suffering atoned for sins committed in a previous carnation of his soul. In summary, we see from the verses and commentators that Iyov was fundamentally a good person. His “sin”, even if it existed, was a slight aberration from the basic foundation of his righteous personality.

This midrash teaches us that when we think of the Jewish people as “Zion” we must think of them the same way. Yes, the Jewish people committed grave sins. Yes, from one perspective they were deserving of punishment. But when one taps into the “Zion” at the heart of their souls, these sins must be seen as an aberration. Zion itself is holy and pure, God’s home on this world. Sins occur and the Jewish people must be exiled as a result, but, similar to Iyov, the basic identity is “sincere, upright, God-fearing and shunning evil.”

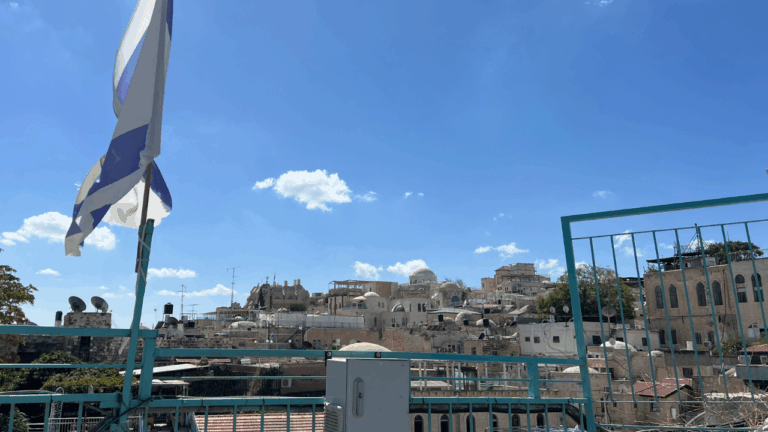

It is for this reason that Yirmiyahu can deliver a message of comfort in the moments right after the destruction. The woman who embodied Zion seemed lost and disheveled. But Zion is always fundamentally connected to God and therefore the conclusion of the story is inexorable. God will return to Zion, rebuild it, and bring His people back home.