Rebbe Eliezer: A Burning Love for Jerusalem

The Shabbatot on which we read the Torah portions of Achrei Mot and Kedoshim present a strange anomaly in the typical haftorah cycle (the haftarah is a portion of scripture that is read after the weekly parsha in the synagogue on Shabbat). Normally, when two parshiyot are read together, the haftarah for the second Torah portion is recited instead of the first. And yet, in years where Achrei Mot and Kedoshim are read together as one parsha, we deviate from this custom and read the haftarah of Parshat Achrei Mot instead of Kedoshim. (This custom is codified by the Rama, the great Rav Moshe Isserlis from Krakow, in Orach Chayim 428:8.)

The Mishna Berura explains that this anomaly is due to the particularly negative rebuke that is found in the haftarah portion of Kedoshim. This haftorah is taken from Yechezkel chapter 16, beginning with the haunting words of בן אדם הודע את ירושלם את תועבתיה, Son of man, inform Jerusalem of her abominations. We deliberately attempt to avoid reciting this portion, instead opting for the more positive portion of Achrei Mot (which comes from the prophet Amos). This is a slightly surprising change, especially given the reality that most haftarot also contain stinging rebuke. Why are we so sensitive about this chapter in Yechezkel particularly?

The customs of Israel take an even stranger turn in unique years such as this, where the two Torah portions are read separately. We would expect that we would read the haftorah of הודע את ירושלים this coming Shabbat and not the haftarah from Amos which we already read last week. And yet, Rav Soloveitchik tz’l recalled that as a child in Lithuania, his esteemed grandfather and father would instruct the congregation to read the same haftorah from Amos again. They were so desperate to avoid Yechezkel chapter 16 that they would repeat the same portion from Amos two weeks in a row! This practice was not unique to Lithuania. It is recorded that Rav Shmuel Salant, the great chief of rabbi of Jerusalem, insisted on the same practice in the holy city. (It is important to note that most congregations do not follow this custom; congregants are encouraged to follow their shul minhag and not to make a fuss after Torah reading this Shabbat…)

What is the motivation behind these extremely anomalous practices? Why are we avoiding the verses of הודע את ירושלים?

The Rav pointed to a powerful passage in the Gemara Megillah (25b) in which the great Rebbe Eliezer ben Hurkinus ruled that it is prohibited to read this portion of Yechezkel publicly. The Gemara recounts that a man once read this portion of Yechezkel in front of Rebbe Eliezer. The great Tannaitic sage chastised him, “before you examine the abominations of Jerusalem, go and examine the abominations of your own mother.” In fact, this man was found to have problematic lineage.

It is true that many haftorot contain intense rebuke of the Jewish people. But in this passage of Yechezkel, the sins of the Jewish people are portrayed as staining the name of Jerusalem. Our abominable actions contaminate the holiness of the city. While it may be true that Yechezkel needed to share such a message, and we must recognize that our actions impact upon the holiness of the land and Jerusalem, Rebbe Eliezer was extremely zealous about protecting the reputation of Jerusalem.

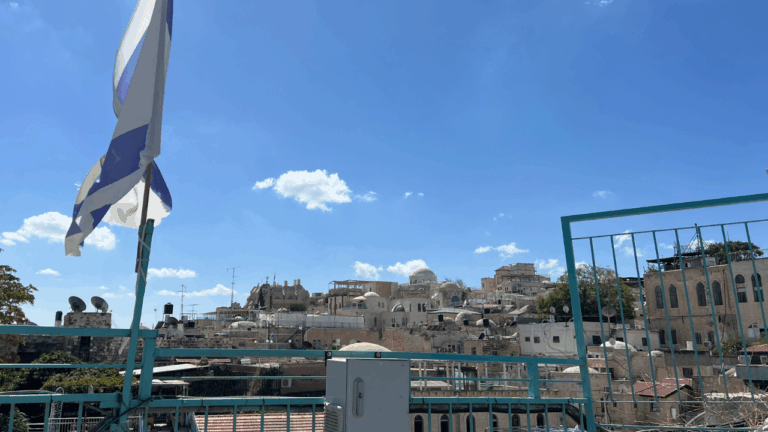

Rebbe Eliezer’s connection to Jerusalem ran very deep. The midrash tells us (Pirkei D’Rebbe Eliezer chapter 1) that Eliezer was a 28-year-old ignoramus who desperately wanted to learn Torah. Depressed and despondent over the meaninglessness of worldly pursuits, he would cry as he worked in his wealthy father’s fields. Despite his father’s strenuous opposition, Eliezer absconded to the holy city of Jerusalem to learn at the feet of the great Rebbe Yochanan ben Zakkai. He arrived as a penniless, smelly, and illiterate pauper. But it was in Jerusalem that Eliezer became the great sage known as Rebbe Eliezer. The holy city nurtured him. It molded him into the chavruta of Rebbe Yehoshua and the teacher of Rebbe Akiva.

While we rarely codify the positions of Rebbe Eliezer, his sensitivity to Jerusalem is something that we should all feel. Jerusalem is the source of our existence, the city that nurtured us and forged us. We should feel zealous for the honor and glory of Jerusalem. We should be terrified of our actions defiling her reputation. And we should always yearn desperately for her complete restoration. May we speedily see the days where the ending of Yechezkel’s prophecy comes true, “I will remember My covenant with you in the days of your youth, and I will establish for you an everlasting covenant.”